A piece I am proud to present, which was written two weeks back now.

One&Other gave me some wriggle room and - following the HMV crises - allowed me to write something that I hope will provoke discussion:

“For

a collector – and I mean a real collector, a collector as he ought to

be – ownership is the most intimate relationship that one can have to

objects”. Walter Benjamin, 1992.

Yesterday I sat in my usual

pub, in my usual chair by the fireplace. I took a swig of scotch and

tensed as the burn caught the back of my throat. Across the room two of

the regulars were locking horns. After several minutes tones elevate and

hands flail, moving light-hearted gents’ banter into a full-blown war:

in one corner, the traditionalist – unkempt and sporting a Genesis

t-shirt and a Walkman held together with tape; in the other corner, the

modernist – white ear buds hanging from his shirt collar, using names

like ‘Spotify’ and ‘Apple’ as verbal cannon fodder. The fact is that

debates over the format and distribution of music have moved beyond the

realm of barstool chatter to serious academic exchanges, and as such, my

mind was in two camps when I was asked to write this article. My first

thought was that somebody somewhere must have placed a serious bounty on

my head in approaching such a contentious topic; the second was simply

‘where the devil am I to start’? It is very easy to sound evangelical

when discussing physicality in record buying, however, and without

wanting to come across too academic, I will endeavour to avoid too many

jingoisms. That said, as I sit now in a room replete with CD cases, dust

jackets and cassette boxes, I suppose it is fairly obvious on which

side of the fence I reside. When HMV announced its administration

earlier this month, my personal Facebook and Twitter accounts were rife

with sobs from friends – those who defected to online outlets still

found themselves mourning the loss of Britain’s most recognised

multimedia store. It has always been de rigueur amongst music diehards

to belittle the franchise for its commerciality and unashamedly

mainstream focus, but because of that very position in their

consciousness, its demise has been a hammer blow to both high-street and

independent record buyers alike. For those of us who still enjoy

filling our shelves, we appear more determined than ever to cling on to

high-fidelity means of music consumption.

In record purchasing,

ownership is a highly tactile, conspicuous experience. The act of

physically ‘picking up’ your item and paying for it – or vice-versa, if

you’re using a website – is a strangely personal one; the £9.99 exchange

leaves you with something you can touch, an acquisition an experience

in its own right. Whatever your poison, an album sleeve potentially

colours your listening – from the fantastical landscapes of Roger Dean

[Yes] to the stark brilliance of Peter Saville [Joy Division], the

listener can choose to envelope themselves sonically and visually within

something tangible, that really is theirs. A far cry came in September

last year when the Sunday Times published an article challenging our

ideas of ownership in digital music consumption. Silver screen veteran

and known music collector Bruce Willis allegedly sought legal action

upon discovering that his extensive iTunes library would revert to Apple

when he dies, unable to pass it on to his family. Though the lawsuit

was promptly dispelled as folklore, the article provoked quite a

reaction with readers learning that those files and folders didn’t

actually belong to them.

When discussing purchasing, I used the

second adjective for a reason: coined by economist Thorstein Veblen in

1899, ‘conspicuous consumption’ is something increasingly practised by

high-fidelity listeners as we find ourselves fighting against the

digital market. I am certainly guilty, with the mere mention of

‘download’ forcing my hand toward the nearest shop like some unwieldy

defence mechanism. Satirically depicted in Nick Hornby’s ‘High

Fidelity’, the image of the collector has become one of near

introversion: scribbling names, thoughts and dates in a little black

book, unwilling to accept the ever-changing outside world. That is the

cliché, and it can be construed as shallow to some.

Philosopher Walter

Benjamin, from whom I take my tagline, postulated that our collections

form a ‘material biography’ – that our dusty shelves reveal something

unique about us as people. Indeed, my own personal record collection

maps a trajectory that underpins the best part of a decade. Record

ownership is profoundly social, a game of join the dots if you will. In

my first year of university, I played a record by Pink Floyd to a guy I

met at a mixer; the next day he came in with a CD case in his hand,

threw it down onto my bed and said ‘dig this, man – David Gilmour

produced it!’ Like a scene from ‘High Fidelity’, this is a record I can

date with a snapshot of my personal history; a reminder of my first days

as a freshman. Numerous sociological studies have been conducted to

show that digital music libraries can also house such biographies –

Marjorie Kibby’s ‘Collect Yourself’ warrants further exploration.

However, there is nothing as ephemeral as that which can be erased by

pressing a key, casting it off into a silicon no-man’s-land. Record or

even CDs can decay physically just like their owners – scuffs, worn

jackets or a mysterious stain – but ultimately continue to turn with the

aid of the right mechanics.

The wealth of music open to the

digital user is unprecedented – between legal and illegal sources there

exists a boundless, readily available catalogue. Whether it is the

instant gratification this medium provides, or perhaps that you have

access to hours of music without risking disappointment, the appeal is

easy to see: ‘every song you have ever owned in your pocket’ is enticing

and liberating, waving goodbye to your cluttered, cobwebbed storage

spaces. Having no fixed location frees us to take our music on the move,

creating a mobile, ‘imperfect sanctuary’ in which to reside as we

traverse our environments.

The choice afforded by your friendly

neighbourhood record shop is always going to trumped by, say, the Apple

store, but like the self-service supermarket, an interface can only take

us so far before we require the services of a sentient being. Software

can offer us suggestions, but it cannot ‘recommend’ to us in the same

way; your local record junkie is always on hand to say ‘hey man, if you

like this band, try the guitarist’s new solo album’ – if the projects

are stylistically different, it is unlikely that a buzzword-based

computer system will make the connection.

Operating economist

Nigel Thrift’s ‘technological unconscious’, it is only when you begin to

analyse the complexity of the processes involved, that user-friendly

cracks appear. If these processes fail – power cuts, computer viruses

and the like – our collections become dormant and isolated. I will never

forget the week I spent carefully ordering my CDs and vinyl onto a

portable hard-drive, only to be met with the message ‘your disk has

corrupted and is unable to complete this operation’. Suffice to say I

haven’t bothered a second time. My record collection is my back-up, my

hard-drive – when my mp3 player packs in, I will still have a ground

zero to return to. Call me shallow, but I like having something I can

point to, something of which I can say “I bought that. I sat down and

listened to that on this stereo, with these headphones”. Above questions

of ownership and tangibility however, stands the true vernacular; we

simply enjoy collecting and sharing things.

I believe it is too

dramatic a leap to say that the record as an artefact is dead, and while

file-based formats continue to supersede, a vast cottage industry

exists for those willing to investigate. Giving new salience to

Benjamin’s ideas, I move to suggest that combined, these formats serve

two distinct purposes: my digital collection is the functioning

offspring of what is on the shelf – I can take it out with me and listen

on the move, but always return to the original at the end of the day.

This is the true collection, the one that I continually nurture and

love.

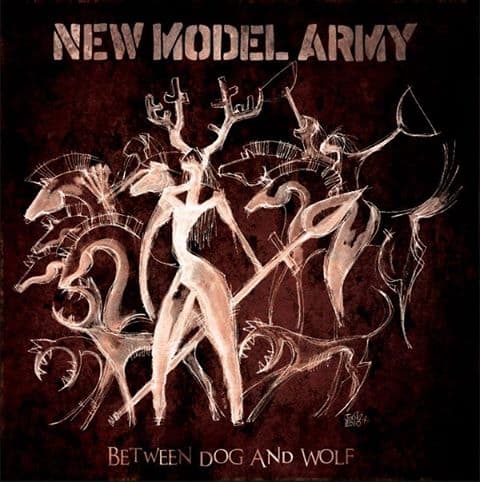

2009's

‘Today Is A Good Day’ was not an empty spectre of a record; nor was it

the ignition of a band firing on all cylinders. In the wake of tragedy,

theft, and departure, Sullivan has weathered a storm, wiped the slate

clean and started again – the result is ‘Between Dog And Wolf’.

Suddenly, the band sounds rejuvenated and purposeful, with new

four-stringer Ceri Monger adding a youthful exuberance to the rhythm

section. The sound is vast and empty, as if the whole band were recorded

in a vacuum. Even at its most visceral, it manages to lift the listener

out of the studio and into the heart of nowhere. From the

cave-painting artwork to the music it contains, ‘Between Dog And Wolf’

is an aural clashing of worlds, of modern and arcane; an observation of

the microcosmic, archaic systems pervading beneath the surface of our

‘Big Societies’.

2009's

‘Today Is A Good Day’ was not an empty spectre of a record; nor was it

the ignition of a band firing on all cylinders. In the wake of tragedy,

theft, and departure, Sullivan has weathered a storm, wiped the slate

clean and started again – the result is ‘Between Dog And Wolf’.

Suddenly, the band sounds rejuvenated and purposeful, with new

four-stringer Ceri Monger adding a youthful exuberance to the rhythm

section. The sound is vast and empty, as if the whole band were recorded

in a vacuum. Even at its most visceral, it manages to lift the listener

out of the studio and into the heart of nowhere. From the

cave-painting artwork to the music it contains, ‘Between Dog And Wolf’

is an aural clashing of worlds, of modern and arcane; an observation of

the microcosmic, archaic systems pervading beneath the surface of our

‘Big Societies’.